Stans vs. Music Journalism (again)

An essay that will piss off the kind of people who'll send you death threats on the internet but are too scared to ask the waiter for more ketchup

Pitchfork published a review of Halsey’s new album, The Great Impersonator, by contributor Shaad D’Souza. While D’Souza did highlight the record’s strengths, his opinion of it was ultimately unfavorable, and a 4.8/10 is a pan regardless.

As has become routine whenever a pop album receives anything less than a stellar review from a major music publication, the stan army descended upon the writer (and/or, as their menacing posts would suggest, the faceless, leviathan entity that is Mr. Pitchfork, the big man himself who writes all the reviews and assigns all of the numerical scores.)

Some of Halsey’s fans voiced anger at the review’s invocation of Halsey’s ex, G-Eazy, in the discussion of a song where Halsey reckons with the dehumanization that comes with being an artist’s muse and a fandom’s idol—in both cases, being viewed as an empty vessel to be looked at but never seen. These concepts are fertile ground for complex, insightful songwriting—something D’Souza writes at length about in his review, discussing the ways this worked in the record’s favor and the ways it didn’t. I don’t think that D’Souza was downplaying the painful experiences that inspired Halsey’s album or that he was wrong to bring them up. Part of the work of a music journalist is to discuss an album in the context of its influences, be they artistic or autobiographical. And for what it’s worth, I’d put money on a lot of those influences that Halsey’s fans deemed off-limits being included in the press materials that her PR team sent out for this album cycle.

In the past ten years or so, pop music has come to favor the personal, the confessional, the gut-spilling. I think that this started from a place of good intentions, of urging listeners and critics to see value in vulnerability. I think it’s a net positive that songwriters—many of whom are women and/or queer or trans people—who were harnessing the inspiration of their life stories and spinning them into compelling music, began to be taken seriously in ways that they hadn’t been before. But this shift showed its insidious side when confessionalism began to overshadow craft, treating autobiographical or deeply personal records as nothing more than pages torn from the artist’s diary. This type of reception disregards the intentionality and skill that goes into making a work of art, and at worse, it gives fans a false sense of familiarity with artists and an expectation that that familiarity should always be reciprocated.

Another pitfall of this phenomenon was that pop music morphed into a sort of Trauma Olympics, of who could tell the biggest sob story—bonus points if it involved seeding blind items about who burned who. Don’t get me wrong, there are many pop records from the past couple years that draw inspiration from the artists’ real life hardships and conflicts in ways that are compelling. Take for example Olivia Rodrigo’s GUTS, which packs so much messiness and complexity into catchy, tightly-coiled pop-rock songs that show Rodrigo’s careful study of her musical influences alongside her capacity for emotional honesty.

I balk at the overemphasis of “relatability” in music (and art in general), and am turned off when an artist seems to be tripping over themself to prove that they really are just like anybody else—as is a major flaw of many pop albums from this year. I’m fascinated by pop stars like Charli XCX and Lana Del Rey and SZA, who seemingly have no interest in convincing fans of their own normalcy, which makes their moments of emotional vulnerability ring truer than the everygirl act that someone like Taylor Swift has been playing for nearly her entire career. To be fair, when she first started out, she was believable as the girl next door. But it’s 2024. You’re not a “tortured poet” if you’re taking a 10-minute private jet ride to go hang out with your NFL boyfriend.

And yeah, at this point, I’ve grown weary of songs about pop stars meditating or going to therapy. I have to stop myself from rolling my eyes each time I see a press release in my inbox that uses pop psychology speak, discussing how this album is a “radically vulnerable” document of the artist’s “healing journey.” And if I have to hear one more song about somebody’s Saturn Return I’m gonna rip my ears off (We get it, you’re freaked out about turning thirty! Join the club! At least write about it in a way that we haven’t heard a million times before!) I don’t want to become desensitized to well-crafted and resonant explorations of heartbreak, trauma, and emotional pain in song—in fact, some of my favorite pop (or alt-pop) records from this year are great because of how they use personal hardships as inspiration (Madi Diaz! Eliza McLamb! Rachel Chinouriri! Charly Bliss! The aforementioned Charli XCX!).

I don’t think that just because a piece of art is inspired by pain or trauma, it has inherent creative merit. To believe this would be to disregard the work of being an artist, to reduce someone’s art to just their pain, and that feels far more disrespectful and dehumanizing than panning their record. I can empathize with someone’s suffering without having that empathy translate into an appreciation for their art. Your therapist and your friends will validate your feelings—you don’t need a music critic to do that.

I also have a bone to pick with famous artists—artists who have millions of dollars and millions of fans that worship the ground they walk on—egging their fans on to go after journalists for doing their jobs. Halsey knew what they were doing when they posted a clapback-y tweet about D’Souza’s review of their album. It’s irresponsible and it’s the kind of thing that you should keep in the group chat (frankly, “keeping it in the groupchat” is a skill that a LOT of us could stand to brush up on, myself included).

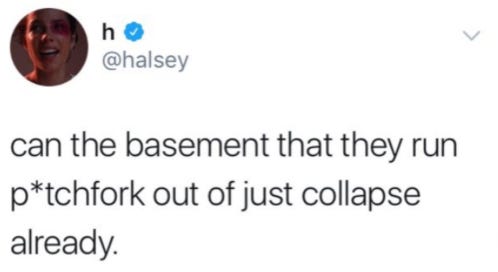

This isn’t the first time Halsey’s expressed a specifically anti-Pitchfork sentiment. Back in 2020, they responded to a 6.5 review of their album Manic with a now-infamous tweet inadvertently calling for another 9/11. Admittedly, that one was pretty funny.

I’ve seen music journalists get doxxed, called slurs, and have their lives and loved ones threatened over less-than-positive reviews. An artist as tapped-in as Halsey knows—at least on some level—that their fans will do these things. Halsey’s written songs about the stress and alienation of having fans project their own feelings onto a pop idol. To critique that type of parasocial fan behavior on the record but then turn around and weaponize it is pure hypocrisy. It’s Halsey telling their fans that it’s okay to be cruel and antisocial towards a stranger, just so long as that stranger isn’t Halsey themself.

It’s not a coincidence that this era in which critics risk getting harassed and endangered for doing anything less than showering praise upon pop stars is also an era in which music criticism publications are shutting down en masse and music journalism has all but ceased to exist as a feasible career path. I’m not saying that the stan armies are responsible for mass layoffs and the slow decline of media journalism outlets (correlation not causation) but both are symptoms of a larger culture of anti-intellectualism. To be anti-arts criticism is to be anti-art.

I’ve seen some fans—and artists—say that we should stop reviewing music altogether. To that I ask: Should we stop reviewing books too? How about films? TV shows? Should restaurant critics only ever pick up their pens to say “the food was delicious, compliments to the chef!”? When did we decide that “If you don’t have anything nice to say, don’t say anything at all” should apply to the entire longstanding tradition of cultural criticism?

I won’t pretend that Pitchfork and music journalism as a whole doesn’t have a long history of making uncharitable, uncalled for, and sexist/racist/otherwise discriminatory remarks toward artists from marginalized backgrounds. In the past decade or so, we’ve seen a lot of long overdue course correction in that regard. But we shouldn’t throw the baby out with the bathwater. Worthwhile criticism requires the evaluation of negatives and positives, and sometimes, it requires a little bit of shit-talking. Can you imagine how boring it would be if every album review ended with “In conclusion: I loved it! Yayyyyyyyyyyyyy!” (Okay actually now that I’ve spoken that idea into existence it’s become my mission to close a review with those exact words).

There is a place for the pans as much as there is a place for the 10/10s. To love or hate something and explain why you feel that way, you have to get to know it, really pay attention to it. I love criticism that is, above all else, attentive.

There’s an episode of Glee (I know, stick with me) in which Puck, attempting to woo new show choir recruit Lauren Zizes, gives her a box of chocolates for Valentine's Day. She shoves the now-empty box back into his hands at the end of class and tells him that the chocolates “sucked.” He protests: “But you ate them all!” Lauren replies, “I had to make sure they all sucked.” It’s an oversimplification, but this scene feels like an apt metaphor for how I feel about the art of writing a negative review.

In a similar vein to my earlier tirade against relatability (“Against Relatability” is the working title for an essay I’ve gotta get around to writing), we should all be engaging with works of art and writing that pull us outside of ourselves and our pre-existing ideas. Some of my favorite pieces of music criticism are pans of records I love and glowing reviews of records I just do not get. I don’t need to relate to something or even agree with it to recognize its intellectual or stylistic merit.

And if music journalism truly means nothing to you and you genuinely believe that it’s not culturally relevant, then why are you getting so aggro about your favorite artist getting panned? I know full well that if that Halsey album had gotten Best New Music, those same fans would be pointing to the review as evidence of the record’s brilliance. You can’t use the good reviews to affirm your taste and shun them when they don’t do that. Either it matters or it doesn’t. Be happy that someone actually took the time to review the damn album instead of just publishing a video of a monkey pissing into its own mouth.